The OMGWords Endgame: Why More Plies Sometimes Reveal the True Best Move

When playing an OMGWords endgame, it might seem intuitive that looking a few moves ahead will reveal the best sequence of moves. But what if I told you that even if a solution requires only 4 moves to complete, you might need to look beyond those 4 moves to find it? This is exactly what happens when we use algorithms like minimax and alpha-beta pruning to solve endgames.

Let me explain using a concrete example from a recent endgame I solved with Macondo . Macondo is an open-source solver. It can exhaustively solve endgames, 1-in-the-bag preendgames, and do Monte Carlo sims, inferences, and more. It’s the engine that underlies HastyBot and the soon-to-be-released BestBot, which I believe is the best bot on the planet!

The Position

In an endgame, you want to find the best sequence of moves to maximize your score difference, also known as the spread. The goal is to optimize not only our own plays but also consider how our opponent might respond.

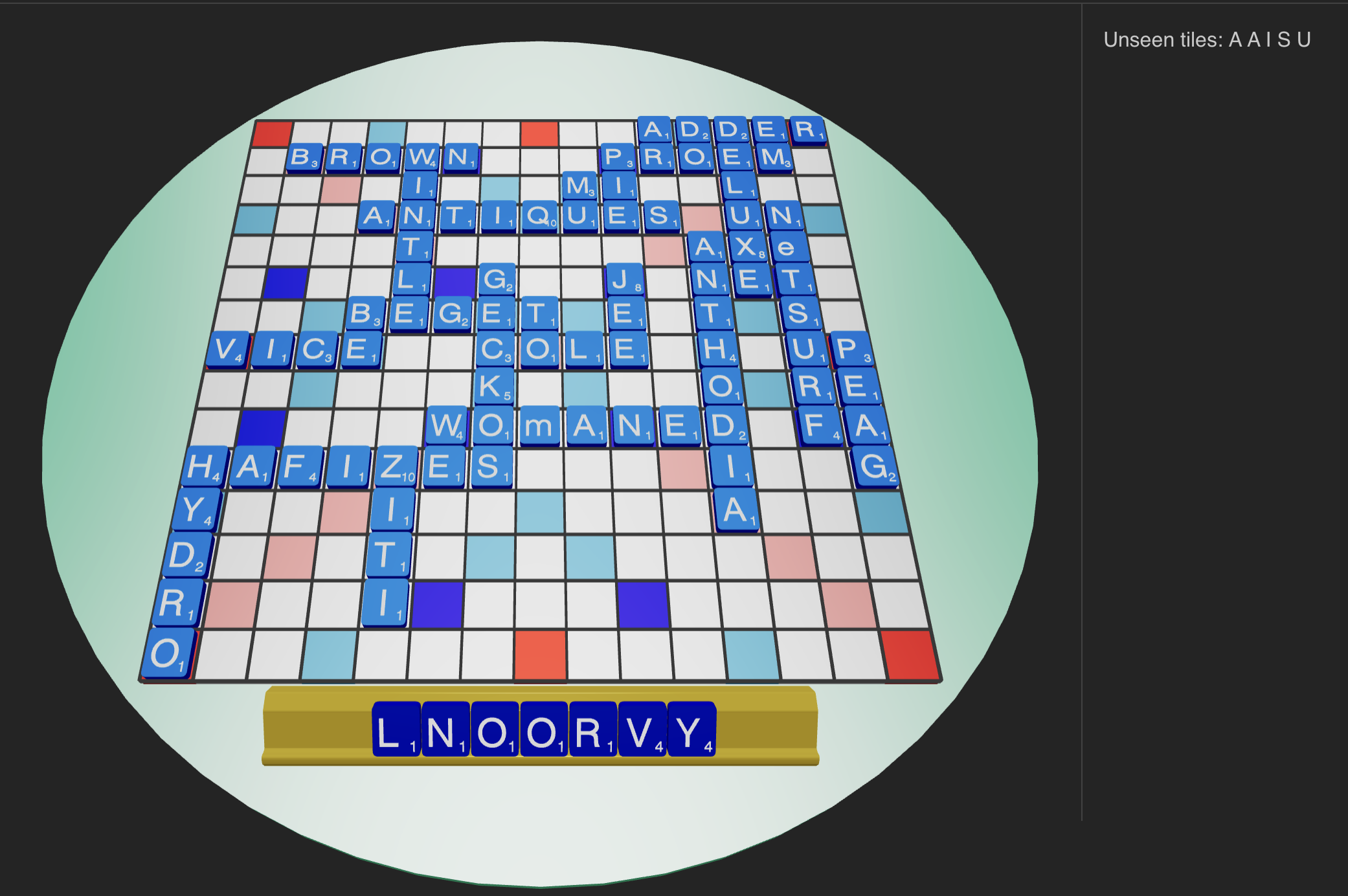

The position looked like this:

Our best move here is “3D V(I)OL” for 20 points.

From there, we need to evaluate our opponent’s possible responses and determine the best sequence to follow up with.

By default, Macondo’s endgame algorithm searches 4 plies ahead (just type in endgame into the command line). However, while this depth seems like enough, it turns out that the best sequence is only found by looking 5 moves ahead.

The Best Sequence: Found with a 5-Ply Search

Here’s the correct sequence, which was only discovered when the algorithm was able to look 5 plies ahead (use endgame -plies 5):

- We play “3D V(I)OL” for 20 points.

- The opponent responds with “15C AAS” for 18 points.

- I then play “10B YO” for 31 points.

- The opponent finishes with “13A (D)UI” for 8 points.

The final result leaves us with a spread difference of +21 and a final score differential of -69. This is the best possible outcome in this situation.

The Wrong Sequence: Found with a 4-Ply Search

However, when I limited the search to only 4 plies, the algorithm found a different, suboptimal sequence:

- We still start with “3D V(I)OL” for 20 points.

- The opponent, instead of playing “AAS,” plays “10B AIS” for 16 points.

- We respond with “14E (I)RONY” for 10 points. This sequence leaves us with a spread difference of +18 and a final score differential of -72 — a worse outcome, despite both sequences having the same starting move.

Why Does This Happen? The Power of Depth in Searches

The key difference between the two sequences comes down to how far ahead the algorithm can “see.” In this case, minimax, the algorithm I’m using, is evaluating possible moves by considering both players’ best strategies. Alpha-beta pruning helps speed up the search by cutting off parts of the tree that don’t need to be evaluated (because they won’t affect the outcome).

In a 4-ply search, the algorithm doesn’t look far enough to see the full consequences of our opponent playing “10B AIS.” The move “AIS” looks good in the short term, but it sets up a worse sequence of events for the opponent. To refute “AIS” as a bad move, the algorithm needs to see beyond 4 plies.

Why Do More Plies Help?

By adding just one more ply (looking 5 moves ahead), the algorithm sees that after playing 10B AIS, we can respond with 12D R(I)N. Then they cannot go out and have to play 6E LAG, and then we will go out with M12 YO. We get way more points if this happens. The algorithm realizes that “AIS” is not as good as it first appeared because of the follow-up moves that benefit me more in the long run.

This happens because the evaluation function that estimates the position’s value after a certain number of moves can only account for what it “sees.” In a 4-ply search, it evaluates “AIS” without fully understanding the later consequences - it can only see 2 more plies after AIS. Only by extending the search does it recognize that “AAS” leads to a better overall outcome.

Iterative Deepening: A Solution for Deeper Searches

One way to improve this process is through iterative deepening. This technique performs a series of increasingly deep searches, starting at 1 ply and working its way up. The advantage is that it allows the algorithm to continuously refine its evaluation as it looks further ahead, while ensuring that even if time runs out, it returns the best solution found so far.

In practical terms, this means that if I’m running an OMGWords solver, I can use iterative deepening to ensure that it doesn’t miss deeper, more optimal solutions—even when there’s a time limit.

BestBot uses iterative deepening with a large number of plies and sets the time limit to 3 minutes. That way it’ll almost always find the optimal endgame play.

In conclusion

Endgames are a fascinating puzzle where evaluating the best moves requires more than just looking a few steps ahead. Sometimes, even though the solution is only 4 moves long, you need to look 5 moves ahead (or more) to fully understand it. This is the nature of minimax and alpha-beta pruning in game theory: they require depth to see the whole picture.

So next time you’re stuck in an endgame, remember that the best solution might just be a few more plies away!